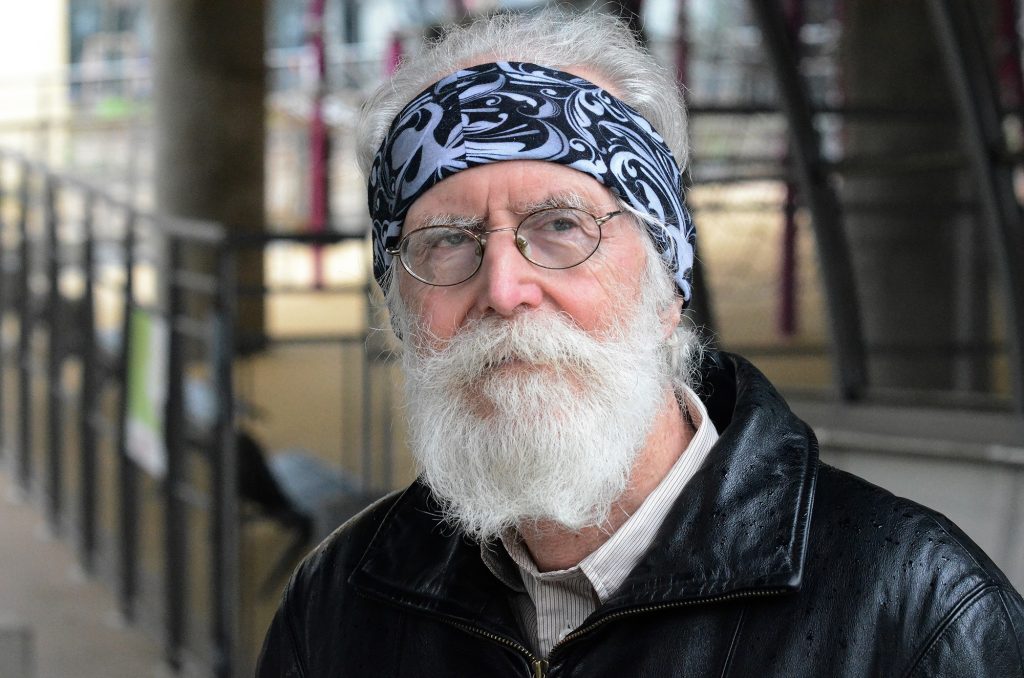

Academic Director of AE-Bergen Hub, Eystein Jansen, at the ERC seminar in Bergen. Photo: Paul S. Amundsen/UIB

For the University of Bergen (UiB) and for the Academia Europaea Bergen Hub, the seminar and ERC board meeting in Bergen on 26th-27th June marked both the end of the first half of 2024 and the beginning of summer. It also concluded a very active season for the AE Bergen Hub.

Our Academic Director Eystein Jansen, who is also the Vice-President for Physical Sciences and Engineering at the ERC, played a key role in bringing the ERC Board to our hometown of Bergen at the close of the spring semester.

“Frontier research is key to securing Europe’s role in the world, in terms of providing more innovations in society, solving global challenges and securing democratic processes. It has been said that that the creation of the ERC is the best European innovation of recent times, and I think I subscribe to that view.” Eystein Jansen said in his welcome speech at the meeting.

Science diplomacy during crises

In 2024, Academia Europaea Bergen has focused extensively on mapping the conditions for scientific cooperation and science diplomacy during geopolitical crises, with a special focus on Arctic relations. Our report The Future of Science Diplomacy in the Arctic, published in 2023, has led to the Rethinking Arctic collaboration project, funded by a 400 000 NOK grant from UArctic. The project team includes renowned scientists from Europe, Canada and the USA.

The Rethinking Arctic Collaboration project was presented at the Arctic Circle Berlin Forum, on 8th May providing an opportunity for team members to meet in person. The project’s aim is to engage with stakeholders and produce a comprehensive report. Outreach is important, and our proposal for an event at the 2024 Arctic Circle Assembly in Reykjavík, Iceland, from 17th-19th October, was recently accepted amidst strong competition.

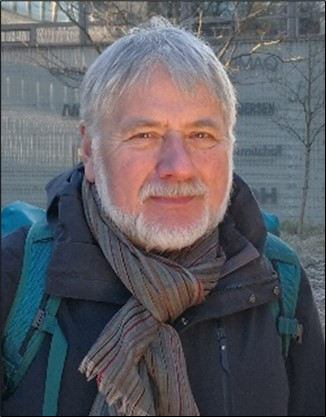

Rector Margareth Hagen, University of Bergen, Maria Leptin, President, European Research Council, and Oddmund Hoel, Minister of Research and Higher Education in Norway at the ERC seminar in Bergen. Photo: Paul S. Amundsen/UIB

Academia Europaea Bergen is committed to expanding our work in Science Diplomacy and Arctic Relations. We have submitted a pre-application for a grant from Nordforsk to fund a 3-4 year project titled Arctic knowledge and knowledge systems in flux – threats and coping strategies for a sustainable Arctic. If awarded, this project will be a truly Nordic effort, with partners from Norway, Finland and Sweden, as well as Trans-Atlantic connections including experts from Canada and the US.

In addition to these major projects, spring 2024 saw Academia Europaea Bergen continue to co-organise a well-established meeting series (mainly held in Norwegian) together with the Bergen offices of the Norwegian Academy of Technological Sciences (NTVA Bergen) and The Norwegian Society of Graduate Technical and Scientific Professionals (Tekna Bergen). Other collaborations included the Horizon Lectures series at UiB and the Arctic Frontiers Conference.

With this summary of our activities at Academia Europaea Bergen, we wish all Members, collaborators and friends a nice summer!

Geir Vollsæter, representing the Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions (LO) of Troms & Finnmark, has more than two decades experience in the oil, gas and power sectors in Norway, Europe, and the US. He recently joined Pharos Advisors following many years at Industry Energy, a union within LO Norway. Energy, power and climate policy keeps him motivated and engaged at work and in civil society.

Geir Vollsæter, representing the Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions (LO) of Troms & Finnmark, has more than two decades experience in the oil, gas and power sectors in Norway, Europe, and the US. He recently joined Pharos Advisors following many years at Industry Energy, a union within LO Norway. Energy, power and climate policy keeps him motivated and engaged at work and in civil society. Sigurd Kvammen Rafaelsen is mayor of Lebesby municipality for the Labor Party. He was born and raised in Kirkenes and moved to Kjøllefjord in 2010. Rafaelsen has been active in politics since he moved to Kjøllefjord. In 2011, he was elected as a municipal board representative in Lebesby municipality. Rafaelsen took over as mayor of Lebesby municipality after the election in 2019. In addition to his role as mayor, Rafaelsen is deputy representative to the National Assembley for the period 2021-2025. He also holds positions as chairman of the National Association of Norwegian Wind Power Municipalities, and as chairman of the Natural Resource Municipalities. He is also deputy leader of Finnmark Arbeiderparti and a board member of Finnmark Havfiske A. Rafaelsen is a teacher by education, and also has a bachelor’s degree in political science as well as a year’s study in German language from UiT – Norway’s Arctic University.

Sigurd Kvammen Rafaelsen is mayor of Lebesby municipality for the Labor Party. He was born and raised in Kirkenes and moved to Kjøllefjord in 2010. Rafaelsen has been active in politics since he moved to Kjøllefjord. In 2011, he was elected as a municipal board representative in Lebesby municipality. Rafaelsen took over as mayor of Lebesby municipality after the election in 2019. In addition to his role as mayor, Rafaelsen is deputy representative to the National Assembley for the period 2021-2025. He also holds positions as chairman of the National Association of Norwegian Wind Power Municipalities, and as chairman of the Natural Resource Municipalities. He is also deputy leader of Finnmark Arbeiderparti and a board member of Finnmark Havfiske A. Rafaelsen is a teacher by education, and also has a bachelor’s degree in political science as well as a year’s study in German language from UiT – Norway’s Arctic University.